Last Updated on January 15, 2023 by Constitutional Militia

As a Rule of Constitutional Construction:

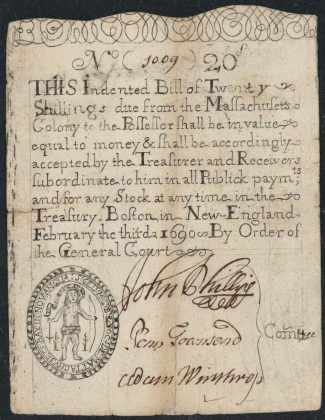

The first step towards elucidating the true meaning of the Constitution’s monetary provisions is not to consult decisions of the Supreme Court, but to study American history preceding the Court’s formation: “to review the background and environment of the period in which that institutional language was fashioned and adopted”.[1] “to place ourselves as nearly as possible in the condition of the [Framers]”,[2] and “to recall the contemporary or then recent history of the controversies on the subject” that “still were fresh in the memories of those who achieved independence and established our form of government”.[3]

The Monetary Powers and Disabilities Under the English Common Law

Pre-constitutional common law is one of the most important legal historical sources of the meaning of many constitutional provisions.[4] During the late 1700s Blackstone’s Commentaries was the standard legal treatise among Americans.[5] Blackstone’s discussion of the English monetary powers was detailed:

[A]s money is the medium of commerce, it is the king’s prerogative, as the arbiter of domestic commerce, to give it authority or make it current. Money is an universal medium, or common standard, by comparison with which the value of all merchandize may be ascertained: or it is a sign, which represents the respective values of all commodities. Metals are well calculated for this sign, because they are durable and are capable of many subdivisions: and a precious metal is still better calculated for this purpose, because it is the most portable. A metal is also the most proper for a common measure, because it can easily be reduced to the same standard in all nations: and every particular nation fixes on it it’s own impression, that the weight and standard (wherein consists the intrinsic value) may both be known by inspection only.

* * * * *

The coining of money is in all states the act of the sovereign power; for the reason just mentioned, that it’s value may be known on inspection. And with respect to coinage in general, there are three things to be considered therein; the materials, the impression, and the denomination.

With regard to the materials, sir Edward Coke lays it down, that the money of England must either be of gold or silver; and none other was ever issued by the royal authority till 1672, when copper farthings and half-pence were coined * * *. But this copper coin is not upon the same footing with the other in many respects * * *.

As to the impression, the stamping thereof is the unquestionable prerogative of the crown * * *.

The denomination, or the value for which the coin is to pass current, is likewise in the breast of the king * * *. In order to fix the value, the weight, and the fineness of the metal are to be taken into consideration together. When a given weight of gold or silver is of a given fineness, it is then of the true standard, and called sterling metal * * *. And of this sterling metal all the coin of the kingdom must be made by the statute 25 Edw. III. c. 13. So that the king’s prerogative seemeth not to extend to the debasing or inhancing the value of the coin, below or above the sterling value * * *. The king may also, by his proclamation, legitimate foreign coin, and make it current here; declaring at what value it shall be taken in payments. But this * * * ought to be by comparison with the standard of our own coin; otherwise the consent of parliament will be necessary.[6]