Last Updated on February 9, 2023 by Constitutional Militia

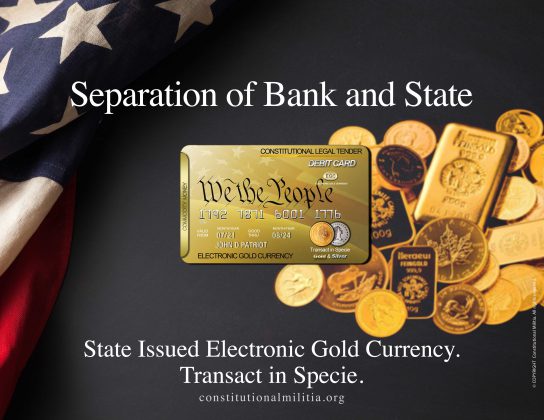

After reading this Introductory Primer, learn how the State Electronic Gold Currency Plan can be implemented in your State and download the Gold Money Bill here.

The State of Montana has modified the Electronic Gold Currency Plan and proposed it in House Bill 639. Learn more here.

I. THE ECONOMIC PROBLEM FACING EVERY STATE TODAY.

The economic problem that confronts every State today can be summarized in a few points:

• The protection of the lives, health, and property of a State’s citizens, and the preservation of good order within the State, depend upon the maintenance of both an adequate system of governmental finance and a sound and robust private economy.

• An adequate system of governmental finance and a sound and robust private economy cannot be maintained in the absence of a sound currency.

• The present monetary and banking systems of the United States, centered around the Federal Reserve System, have come under ever-increasing strain during the last several years, and will be exposed to predictably debilitating, if not utterly destructive, pressures, both domestic and international, in the months and years to come. Actually, the Federal Reserve System’s susceptibility to recurrent and ever-more-serious crises is nothing new. The System suffered its first major crisis in 1932 to 1934, with the abrogation of the domestic “gold standard”. It suffered its next major crisis in 1971, with the abrogation of the international “gold standard”. Each of these events removed one important “governor” from the monetary engine, so that at the present time nothing prevents the System from destroying itself by (as the automotive term has it) “running past the red line”. For that reason, the present crisis promises to be the last, because the System will not survive it.

• The best-informed experts in the theory and practice of money, banking, and both public and private finance predict the unavoidable collapse of the Federal Reserve System’s currency through hyperinflation in the foreseeable future, most likely followed by a depression far more serious than took hold of the national economy during the 1930s.[1]

• In the event of hyperinflation, depression, or other economic calamity related to the breakdown of the Federal Reserve System, a State’s governmental finances and private economy will be thrown into chaos, with gravely detrimental effects upon the lives, health, and property of her citizens, and with consequences fatal to the preservation of good order throughout her territory.

• At the present time, no State is prepared to deal with this problem—because any survey will disclose that vanishingly few, if any, State officials can provide an immediate, unequivocal, and realistic answer to the question: “If the Federal Reserve System collapses in hyperinflation in the near future, exactly what will the State and her citizens then use as their currency?” Not having an answer to this question—or not bending every effort to find an answer as soon as possible—constitutes an admission of irresponsibility and incompetence that should disqualify any public official for the position of trust he holds.

• With proper leadership, however, a State can avoid or at least mitigate many of the economic, political, and social shocks to be expected to arise from hyperinflation, depression, or other economic calamity related to the breakdown of the Federal Reserve System through the adoption of an alternative sound currency that her government and citizens may employ before, and in any event without delay in the event of, the destruction of the System’s currency.

What follows herein will assume for purposes of argument that the Federal Reserve System and its paper currency, Federal Reserve Notes, are constitutional. In fact, however, nothing could be clearer than the unconstitutionality of both those notes and the banking-cartel from which they spring.[2] This, of course, renders the problem even more serious than if it were solely economic in nature.

II. THE RESPONSIBILITY OF THE STATES TO DEAL WITH THIS PROBLEM.

A State not only can avoid or at least mitigate these shocks, but also labors under a legal and moral duty to take every step possible in order to do so: “[I]t is not only the right, but the burden and solemn duty of a state, to advance the safety, happiness and prosperity of its people, and to provide for its general welfare, by any and every act of legislation, which it may deem to be conducive to these ends”.[3]

III. THE GENERAL LEGAL AUTHORITY OF THE STATES TO DEAL WITH THIS PROBLEM.

Each State enjoys the full measure of legal authority necessary and sufficient to deal with the consequences of a breakdown of the Federal Reserve System. At the most basic and general level, that authority inheres in the State’s so-called “police power”.

A. “The police power” “is a power originally and always belonging to the states, not surrendered by them to the general government, nor directly restrained by the Constitution of the United States, and essentially exclusive”.[4] “The police power” “is not granted by or derived from the Federal Constitution, but exists independently of it, by reason of its never having been surrendered by the states to the general government”.[5] The States possess “the police power” “in their sovereign capacity touching all subjects jurisdiction of which is not surrendered to the federal government”.[6] So, in its broadest interpretation, “the police power” subsumes all of the sovereign powers of a State government reserved to it by the Constitution of the United States. It is, therefore, the primary subject of the Tenth Amendment with respect to the States, because it embraces all of “[t]he powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, [which] are reserved to the States respectively”. That being so, “the police power” is “one of the most essential of powers, at times the most insistent, and always one of the least limitable of the powers of government”.[7]

B. The practical reach of the States’ “police power” is broad indeed. It “extend[s] to the protection of the lives, health, and property of the[ir] citizens, and to the preservation of good order”,[8] and “embraces regulations designed to promote the public convenience or the general prosperity, as well as regulations designed to promote the public health, the public morals, or the public safety”.[9]

Of particular concern in the realm of economic activity,

the police power extends to all the great public needs. * * * It may be put forth in aid of what is sanctioned by usage or held by * * * preponderant opinion to be greatly and immediately necessary to the public welfare. Among matters of that sort probably few would doubt that both usage and preponderant opinion give their sanction to enforcing the primary conditions of successful commerce.[10]

Thus, because “the prevention of deception is within the competence of government” through exercises of “the police power”,[11] “the police power” can be invoked and applied “to prevent frauds and to require honest weights and measures in the transaction of business” and “in the sale of articles of general consumption”,[12] and “with a view to preventing fraud and facilitating commercial transactions”.[13] Moreover,

the power of the state to prevent frauds and impositions * * * applies as well to securities as to material products * * * . As to material products the purpose may be accomplished by a requirement of inherent purity. The intangibility of securities, they being representatives or purporting to be representatives of something else, * * * requires a difference of provision, and the integrity of * * * securities can only be assured by the probity of the dealers in them and the information which may be given of them.[14]

Finally, “the police power” can be employed for “the protection of a large class of laborers in the receipt of their just dues and in the promotion of the harmonious relations of capital and labor engaged in * * * industry in the state”.[15]

C. Of course, “the police power” must always be exercised consistently with due process of law. “[T]he guaranty of due process”, however,

demands only that the law shall not be unreasonable, arbitrary or capricious, and that the means selected shall have a real and substantial relation to the object sought to be attained.

* * * * *

So far as the requirement of due process is concerned, and in the absence of other constitutional restriction, a state is free to adopt whatever economic policy may reasonably be deemed to promote the public welfare, and to enforce that policy by legislation adapted to its purpose. The courts are without authority to declare such policy, or, when it is declared by the legislature, to override it.[16]

And a State’s “economic policy” may be as extensive and comprehensive as her legislature deems the prevailing conditions may warrant.[17]

IV. THE SPECIFIC AUTHORITY OF THE STATES TO ADOPT AN ALTERNATIVE CURRENCY.

A. The ultimate purpose of a State’s adoption of an alternative currency would be to protect the economic, social, and political well-being of her citizens in the event of a collapse of the Federal Reserve System and the destruction of its currency (Federal Reserve Notes) in hyperinflation. To this end, “the police power” is particularly well suited.

First, “the police power of a state embraces regulations designed to promote * * * the general prosperity”[18] and “to enforc[e] the primary conditions of successful commerce”[19]—and in a free-market economy “the general prosperity” cannot be advanced through “successful commerce” without a politically honest and economically sound medium of exchange.

Second, with respect to “the general prosperity”, nothing is more important than securing the economic well-being of average citizens, the bulk of whom are wage-earners or salaried employees—and a politically honest and economically sound medium of exchange is necessary to “protect[ ] * * * laborers in the receipt of their just dues and in the promotion of the harmonious relations of capital and labor engaged in * * * industry”.[20]

Third, “the police power” should be applied with especial rigor “to prevent frauds and to require honest weights and measures in the transaction of business”,[21] “in the sale of articles of general consumption”,[22] and “with a view to * * * facilitating commercial transactions”[23]—because, inasmuch as money is the one article in which the prices of all “articles of general consumption” are stated in a free-market economy, an inextricable connection ought always to exist between honest weights and measures and money. Indeed, the Constitution itself recognizes as much, when it conjoins the two in the power it delegates to Congress “[t]o coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures”.[24] Self-evidently, the Framers understood that “regulat[ing] the Value” of domestic and foreign “Coin” is not simply akin to, but indeed is a special case of, “fix[ing] the Standard of Weights and Measures”; that the scientific principles of verifiability or falsifiability applicable to the latter also apply to the former; and that therefore any purported medium of exchange not capable of satisfying those principles is inherently defective in character and ultimately unworkable in the marketplace.[25]

For example, the intrinsic “Value” of a gold or silver “Coin”—that is, the weight and fineness of precious metal it contains—not only is fixed in principle but most importantly can be verified or falsified chemically or physically in practice by anyone, anywhere, at any time to whatever degree of accuracy his equipment allows. And, assuming the honesty and competence of the mint striking such a “Coin”, its “Value” can be safely ascertained for most purposes simply by visual inspection. Whereas, in stark contrast, the exchange-value in gold or silver (or in any other commodity, for that matter) of a contemporary Federal Reserve Note, even if emitted by the most honest and competent bankers, depends entirely upon contingent circumstances—being one amount today, another tomorrow; and even different amounts in different places on the same day. No one holding a Federal Reserve Note can possibly predict exactly what value in any commodity it will represent at any future time. Whereas, any holder of a gold or silver “Coin” knows its precise, unchanging “Value” at all times, both present and future.

Fourth, of particular significance today should be the employment of “the police power” “to prevent frauds and impositions” with respect to those “securities” that pass as currency, with an aim to insure the “integrity of * * * [such] securities” by regulation of “the probity of the dealers in them and the information which may be given of them”[26]—or, if such insurance is impossible, to replace that currency with something better. Contemporary Federal Reserve Notes are “obligations of the United States”, and therefore constitute governmental “securities” of a sort.[27] Common sense teaches that it would be far more efficient and effective for Americans to stop using such “securities” as currency, and instead to insist upon the commodities gold and silver, which are assets and not anyone’s debt. For, at a minimum, “the probity of the dealers in them and the information which may be given of them” will be far easier to ascertain and control with respect to a mint striking coins according to the principle of “free coinage”,[28] than to an agency such as the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “issu[ing] at [its] discretion” paper currency “for the purpose of making advances to Federal reserve banks”.[29]

Moreover, experience over nearly a century has amply demonstrated that, in the final analysis. “the probity of the dealers in [Federal Reserve Notes] and the information which may be given of them” cannot be guaranteed to a satisfactory degree. Rather, as current events attest, the bankers in the Federal Reserve System and their clients in “the financial community” have proven themselves shockingly deficient in probity, transparency, responsibility, accountability, and even basic competence. Bad enough that, even in tranquil times, they regularly manipulate monetary aggregates, interest rates, and related matters for economic and political ends favorable to their own special-interest group and the public officials who support them—indeed, the Federal Reserve System’s so-called “monetary policy” is designed for that very purpose. Worse yet, in times of crisis brought about by their own irresponsible actions—such as America is now suffering through—they go even further, demanding exorbitant “bail outs” from the public fisc to save them from the consequences of their own profligacy. Worst of all, analysis of the root causes of the present crisis exposes almost the entire “financial sector” of the national economy as riven with “Ponzi schemes”, gambling agreements disguised as “securities”, various species of investment frauds, “money laundering”, and other corrupt practices effectuated through or otherwise facilitated by the banking system. At base, most of these schemes depend upon the character of Federal Reserve Notes as “an I.O.U. nothing currency”, the supply of which can be expended almost without limit, because neither the Federal Reserve System nor the United States Department of the Treasury is required by law to redeem those notes in any fixed amount of gold or silver.[30]

Fifth, the present statute that defines the character of Federal Reserve Notes requires that they be redeemed only in “lawful money”, which need not be gold or silver, and conceivably could be any intrinsically worthless thing to which Congress attached that label.[31] And the General Government claims the absolute rights neither to pay out gold or silver coin in exchange for other forms of currency, nor to allow anyone to bring suit on the matter.[32] So, absent amendment of these provisions (the likelihood of which in the immediate future is essentially nil), common Americans cannot expect a reform in this country’s monetary and banking systems in the direction of reintegrating gold and silver into the economy as actual currency usable in day-to-day transactions—at least before the Federal Reserve Note is destroyed in hyperinflation, and this country’s entire economy with it.

Which leaves the problem for the States to solve. That, however, is not as dire a situation as it might appear at first glance, because, as the foregoing explains, any State’s “police power” can be applied to provide her public and private sectors with an alternative economically sound and politically honest currency based on gold and silver. For the adoption of an alternative currency is an economic policy; and, “in the absence of other constitutional restriction, a state is free to adopt whatever economic policy may reasonably be deemed to promote the public welfare, and to enforce that policy by legislation adapted to its purpose”.[33]

B. No “other constitutional restriction” stands in the way of such a reform. Indeed, quite the opposite. The Constitution plainly permits—and if it is to be strictly enforced even requires—a State to adopt an alternative currency consisting of gold and silver that can compete with, and if necessary wholly supplant, Federal Reserve Notes in the financial transactions of the State’s government and in the commercial transactions of her citizens in the private economy. Each and every State, for herself and her citizens, is constitutionally (as well as in some particulars statutorily) authorized:

1. to adopt gold and silver coin as alternative currency;

2. to adopt “electronic gold” and “electronic silver” as alternative currency;

3. to avoid the use of whatever the General Government has designated “legal tender”, to whatever degree may be desirable;

4. to employ so-called “gold-clause contracts” even to the exclusion of contracts payable in Federal Reserve Notes, base-metallic coins, or other forms of currency that do not consist of gold or silver; and

5. to enjoy permanent and untrammeled access to the gold and silver necessary for these purposes.

In considering each of these matters, one must focus squarely on the Constitution’s monetary powers and disabilities: namely,

ARTICLE I, SECTION 8, CLAUSE 5 — “The Congress shall have Power * * * [t]o coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures[.]”

ARTICLE I, SECTION 10, CLAUSE 1 — “No State shall * * * coin Money; emit Bills of Credit; make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts[.]”

1. The States’ power to adopt gold and silver coin as alternative currency.

a. The States possess “the police power” “in their sovereign capacity touching all subjects jurisdiction of which is not surrendered to the federal government”.[34] The States’ “jurisdiction”—that is, their legal authority—to employ gold and silver coin as alternative currency is a “subject[ ] * * * which is not surrendered to the federal government”. Rather, the Constitution itself explicitly reserves that power to the States, in absolute terms.

(1) Article I, Section 10, Clause 1 of the Constitution provides that “[n]o State shall * * * coin Money; emit Bills or Credit; make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts[.]”[35] So, on the very face of the Constitution, the States may “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender”—and, according to the principle that the Constitution must always be read with an eye towards fully achieving its purposes, the States should always “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender”.[36]

True it is that the authority to “make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender” is drafted as an exception to the States’ general disability to “make * * * Tender[s]”—that is, as an exception to an absence of power. But an exception to an absence of power is necessarily the recognition of that power to the full extent of the exception. And the exception in favor of “gold and silver Coin” knows no bounds in terms of the times at which, the circumstances in which, or the degree to which the States may apply it. So the States may and should “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender” under all appropriate circumstances, and especially under the near-calamitous conditions prevailing in America today. For WE THE PEOPLE would never have reserved that power to the States in the first place unless they intended the States to use it whenever necessary.

Now, “Tender” is generally defined as “[a]n offer of money; the act by which one produces and offers to a person holding a claim or demand against him the amount of money which he considers and admits to be due, in satisfaction of such claim of demand, without any stipulation or condition”. And “[l]egal tender is that kind of coin, money, or circulating medium which the law compels a creditor to accept in payment of his debt, when tendered by the debtor in the right amount”.[37] So, perforce of Article I, Section 10, Clause 1, the States may not compel a creditor to accept in payment of any “Debt[ ]” solvable in money “any Thing but gold and silver Coin”, but may compel him to receive such “Coin”. With, however, one important exception: If a creditor and a debtor have already entered into an enforceable contract which specifies as the exclusive medium of payment something other than gold or silver coin, no State can compel them by some subsequently enacted law to substitute any other medium of payment, including gold or silver coin—because Article I, Section 10, Clause 1 also declares that “[n]o State shall * * * pass any * * * Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts”. Moreover, as will be explained below, the States cannot be compelled by the General Government not to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender”, or to “make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender”, within their jurisdictions either as to their own transactions as part of the public business or as to the transactions of their citizens in the private economy.

(2) Because it is directed towards promoting “the general prosperity”, the States’ power to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender” is necessarily as exhaustive as their “police power”. Perhaps most importantly in this regard, except in one respect, the Constitution in no way limits the ambit of the States’ authority to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender” with respect to the possible sources of such “Coin”. The only “gold and silver Coin” excluded from the States’ power to “make * * * a Tender” is the “Money” which the States themselves might purport to “coin”, because Article I, Section 10, Clause 1 prohibits any actual State coinage in the first place. Otherwise, “where no exception is made in terms, none will be made by mere implication or construction”.[38] Therefore, the domestic “Coin” Congress causes to be minted, the “foreign Coin” the “Value” of which Congress “regulate[s]”, and even private “Coin”—as long as they consist of gold or silver—are all fit subjects for the States’ power to “make * * * a Tender”. The States may declare any and every domestic “gold and silver Coin a Tender”, in addition to any relevant declaration Congress has put forth. The States may declare any and every foreign “gold and silver Coin a Tender”, even when (as is the case today) Congress has refused to do so.[39] And conceivably under the broad language of Article I, Section 10, Clause 1, in extraordinary situations the States might declare even any and every private “gold and silver Coin a Tender”, notwithstanding that Congress could not declare any such “Coin” “legal tender” vel non, inasmuch as Congress certainly cannot mint private “Coin” itself, and arguably cannot “regulate the Value * * * of foreign Coin” not minted by a foreign government. For example, if rogue Members of Congress refused “[t]o coin Money” and to “regulate the Value * * * of foreign Coin” to the degree necessary to supply “gold and silver Coin” in amounts sufficient to serve the needs of the States and their citizens, the States would have no alternative but to rely upon private coinage in order to fulfill their duty to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender”, because they could not “coin Money” themselves.

The only condition on the States’ exercise of their power “to make * * * a Tender” is that they must apply it comprehensively to both “gold and silver Coin”. Under Article I, Section 10, Clause 1, a State may not adopt a monometallic “gold standard” or “silver standard”, but must always employ the two monetary metals in tandem in a “gold and silver standard”—and, of course, always in such a manner as to ensure that, in every particular transaction, “a Tender” required to be made in “gold * * * Coin” will deliver the selfsame purchasing power as “a Tender” in “silver Coin”.[40]

(3) The States’ power to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender” is part of their “police power”, and as such “is a power originally and always belonging to the states, not surrendered by them to the general government, nor directly restrained by the Constitution of the United States, and essentially exclusive”.[41] More than that, though, because of its placement in the Constitution, the States’ power to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender” is effectively absolute.

(a) This conclusion finds obvious support in the important differences among the three clauses in Article I, Section 10. The first clause differs significantly from the following two, in that it begins, “[n]o State shall”, whereas the others commence, “[n]o State shall, without the consent of Congress”.[42] On its face, this divergent language imports an absolute prohibition with respect to the matters within the first clause, and a conditional prohibition with respect to the matters within the second and third clauses: Congress may permit or enable the States to do what the second and third clauses of Article I, Section 10 prohibit; but it lacks authority to license or aid—let alone to command—any State to do anything within the first clause. And the States cannot contend that they may violate that clause because Congress has directed them, or provided them with some means, to do so.

The evolution of the Constitution in the Federal Convention of 1787 confirms this literal interpretation.[43] Early drafts of the Constitution licensed the States to emit “Bills of Credit” and to make any thing but specie a tender with the consent of Congress.[44] On 28 August 1787, the Convention took up one proposed draft providing, in relation to monetary disabilities, only that “[n]o state shall coin money”.[45] In James Madison’s words,

Mr WILSON & Mr SHERMAN moved to insert after the words “coin money”, the words “nor emit bills of credit, nor make any thing but gold & silver coin a tender in payment of debts” making these prohibitions absolute, instead of making the measures allowable * * * with the consent of the Legislature of the U. S. [i.e., Congress].

Mr GHORAM thought * * * an absolute prohibition of paper money would rouse the most desperate opposition from its partizans.

Mr SHERMAN thought this a favorable crisis for crushing paper money. If the consent of the Legislature could authorize emissions of it, the friends of paper money, would make every exertion to get into the Legislature in order to licence it.[46]

On the amendment outlawing “bills of credit”, the States voted eight for, one against, one divided; whereas, on the provision pertaining to “tender”, the motion carried nemo constante.[47]

In his report on this evolution to the Maryland Legislature, Luther Martin, an able lawyer who had dissented from the amendment,[48] explained the legal import of the change:

By the tenth section, every state is prohibited from emitting bills of credit. As it was reported by the committee of detail, the states were only prohibited from emitting them without the consent of Congress; but the Convention was so smitten with the paper-money dread, that they insisted the prohibition should be absolute. It was my opinion * * * that the states ought not to be totally deprived of the right to emit bills of credit, and that, as we had not given an authority to the general government for that purpose, it was the more necessary to retain it in the states. * * * I therefore thought it my duty to vote against this part of the system.[49]

If a vote of 8 to 1 in favor of outlawing “bills of credit” rendered that prohibition “absolute”, then certainly an unanimous vote against all “tender in payment of debts” other than “gold & silver coin” could have done no less.

Luther Martin accurately reported “the paper-money dread” with which, not only the Federal Convention, but also the country as a whole “was so smitten”. The Framers of, and WE THE PEOPLE who ratified, the Constitution well knew that the Continental Congress had emitted “Bills of Credit”, that the States had given this (and their own) paper currencies the coercive character of “legal tender”, and that both Congress and the States had forced these currencies and other “Thing[s]” on unwilling creditors in payment of private and governmental debts.[50] Had the Framers and WE THE PEOPLE desired to enable “the friends of paper money” to continue these practices as a matter of political policy, they would have located the phrases “emit Bills of Credit” and “make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts”, not in the first clause of Article I, Section 10, but rather in the second or third clause. They would have established a merely contingent and conditional prohibition—to wit, “[n]o State shall, without the Consent of Congress, emit Bills of Credit, or make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender”—instead of the unconditional prohibition the Constitution actually contains. Their doing the latter rather than the former provides overwhelming proof that they sought the result the plain meaning of Article I, Section 10, Clause 1 requires: that “[n]o State” may treat “any Thing” at all—not necessarily just a “Bill of Credit” or other form of paper currency—as a “Tender in Payment of Debts”, whether that “Thing” is emitted or otherwise employed by a State on her own initiative, or by a State with the purported approval of Congress, or even by Congress itself. The Framers were capable of making very fine distinctions in the area of Congressional authorization of otherwise prohibited State actions.[51] They made no such distinction concerning “Tender[s]”, however.

Not surprisingly, therefore, Justices of the Supreme Court early and repeatedly recognized the absolute nature of the prohibitions in Article I, Section 10, Clause 1. In Ogden v. Saunders, Chief Justice Marshall spoke of that clause as dealing with matters “entirely prohibited”, and as “consisting of total prohibitions” with “no exception from it”.[52] In Poole v. Fleeger, Justice Baldwin referred to the strictures of that clause “which in their terms are absolute, operating, without any exception, to annul all state power over the prohibited subjects”.[53] In Rhode Island v. Massachusetts, the Court noted that “no power under the government could * * * dispense with the constitutional prohibition”.[54] In Holmes v. Jennison, Chief Justice Taney wrote that, in the first clause of Article I, Section 10, “the limitations are absolute and unconditional”, and contrasted it with the second clause, wherein “the forbidden powers may be exercised with the consent of Congress”.[55] Justice Barbour also remarked that the first clause “absolutely prohibits the states” from doing certain things.[56] In Gunn v. Barry, the Court held that “Congress cannot, by authorization or ratification, give the slightest effect to a State law * * * in conflict with” Article I, Section 10, Clause 1.[57] And in Edwards v. Kearzey, the Court emphasized that “[t]he prohibition contains no qualification, and we have no judicial authority to interpolate any”.[58] Moreover, it opined, “[n]o State can invade it; and Congress is incompetent to authorize such invasion. Its position is impregnable, and will be so while the organic law of the nation remains as it is.”[59]

Of course, these decisions did not refer specifically to the phrase “make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts”, but rather to other phrases in Article I, Section 10, Clause 1. The constitutional principle, however, is identical in all cases: Congress may not interfere with fulfillment of any of the duties any of those phrases enjoin, pursuant to any of its powers, and for any reason. Also true is that these decisions addressed the States’ disabilities in Article I, Section 10, Clause 1, and not their reserved power to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts”. But if all of the prohibitions are beyond the power of Congress to set aside, then the States’ reserved authority that inheres in that particular one of them is no less beyond Congress’s power to negate. Therefore, both the States’ duty not to “make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender” and their right, power, privilege, and duty to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender” are equally absolute.

(b) From this it follows that: (i) Only a State can “make any Thing * * * a Tender” in violation of Article I, Section 10, Clause 1—or, conversely, no State can ever interpose any action of Congress as justifying or exonerating her transgression of that Clause in any respect. And (ii) no State can ever interpose any action of Congress as justifying or exonerating her refusal to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender” whenever her citizens’ economic “homeland security” demands it.[60]

(i) Even if Congress itself emits (in the form of Treasury Notes) or causes to be emitted (in the form of Federal Reserve Notes) a paper currency both irredeemable in gold or silver coin and declared to be a “legal tender” for all debts without exception throughout the United States, no State may purport to pay any of her “Debts” to unwilling creditors in that currency and then defend her actions against an attack under Article I, Section 10, Clause 1 on the ground that Congress, not the State, was responsible for “mak[ing]” the currency in the first place, and for endowing it with the character of “legal tender”—because the State enjoys a perfect constitutional immunity against being compelled herself, or compelling any of her creditors, to use that currency.[61]

On the one hand, Congress could, directly or indirectly, emit such a currency, but also declare its use by the States strictly permissive. That is the situation today. Through the Federal Reserve Board and the Federal Reserve System’s regional banks, Congress indirectly emits Federal Reserve Notes, which are not redeemable in gold or silver coin, but which Congress has declared to be “legal tender for all debts, public charges, taxes, and dues”.[62] Through the Treasury, Congress also issues base-metallic coins, which the Treasury refuses to exchange “dollar for dollar” for “gold and silver coins”, but which are also declared to be “legal tender”.[63] Nonetheless, no one other than the government of the United States is required to make contracts payable in either Federal Reserve Notes or base-metallic coins, to the exclusion of gold or silver coins.[64] And, in principle, Congress cannot constitutionally compel the States to use any particular medium of exchange, even one it has designed “legal tender”, in order to perform their sovereign governmental functions.[65] Thus, any State’s payment of her “Debts” with Federal Reserve Notes or United States base-metallic coins is discretionary action of her own that literally fits the description “mak[ing] * * * a Tender”, in the sense of voluntarily choosing something other than “gold and silver Coin” as a medium of payment. In such a case, Congress is no more legally responsible for the State’s actions than the governments of Mexico, Germany, or China would be if the State chose to tender pesos, euros, or yuan to a creditor.

On the other hand, Congress might emit a paper currency irredeemable in gold and declare it to be a compulsory “legal tender” for all “Debts”. This Congress purported to do when it declared Federal Reserve Notes to be “legal tender” (from 1933 to the present), terminated those notes’ redemption in gold for American citizens (from 1933 to today), and outlawed so-called “gold-clause contracts” (from 1933 to 1978).[66] The plain language of Article I, Section 10, Clause 1, however, does not distinguish between voluntary and involuntary State actions: If the State “make[s] * * * a Tender”, in the sense of physically tendering to an unwilling creditor “any Thing but gold and silver Coin” in purported payment of her “Debts”, the State herself violates that clause’s prohibition, notwithstanding that she pleads the ultimate cause of her actions to be some Congressional statute. Even were the paper currency absolutely redeemable in “gold and silver Coin”, and thus constituted warehouse receipts for such coins secured in the public treasury, its use by the States would violate Article I, Section 10, Clause 1, because the paper—which is actually tendered—is a “Thing” other than the “gold and silver Coin” in which a creditor might be able to redeem it at a later date. (Indeed, the currency is an unconstitutional “Bill of Credit”.) So, Article I, Section 10, Clause 1 supports the doctrine of “interposition”—by which a State could refuse to accede to the mandate of a purported “Law[ ] of the United States” not “made in Pursuance [of the Constitution”.[67]

It is, of course, irrelevant which of its powers Congress might assert in aid of attempting to impose some “legal tender” on the States in defiance of Article I, Section 10, Clause 1. For example, notwithstanding the breadth of Congress’s power “[t]o regulate Commerce * * * among the several States”,[68] that power could not be invoked to prevent a State from adopting an alternative currency of “gold and silver Coin” for her own governmental purposes, for at least three reasons:

First, by definition, a State and its governmental operations do not constitute any species of “Commerce” at all—for the former are inherently political, whereas the latter are inherently economic, in nature. If “government” were “Commerce”, then the power “[t]o regulate Commerce” would enable Congress effectively to supersede and effectively become the States’ governments.

Second, an alternative currency adopted by and employed within a single State, for that State’s own governmental purposes, is self-evidently not an activity that takes place “among the several States”.

Third, even if these two conclusive definitional objections could be disregarded for purposes of argument, there remain the considerations that: (i) The States’ power to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts” is part of their “police power”. (ii) “[T]hat interstate commerce is indirectly affected will not prevent the state from exercising its police power, at least until Congress, in the exercise of its supreme authority, regulates the subject”.[69] And (iii) Congress can claim no “supreme authority” to prohibit the States from “mak[ing] * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender”, because “the supreme Law of the Land” has explicitly reserved that authority exclusively to the States. For the power “[t]o regulate Commerce” to be taken to be “supreme” over Article I, Section 10, Clause 1 would require that clause to be misinterpreted to read: “[n]o State shall * * * make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts without the Consent of Congress, or in the Absence of the Disallowance of Congress, expressed through some Regulation of Commerce”. Then Article I, Section 10, Clause 1 would be just as conditional as Clauses 2 and 3. This would be constitutionally nonsensical, though. For if a requirement of “the Consent of Congress” (in any form) could be interpolated implicitly into Clause 1, where that requirement is conspicuous by its absence, its explicit inclusion in Clauses 2 and 3 would be supererogatory, because it could just as easily be interpolated there, too. But “[i]t cannot be presumed that any clause in the constitution is intended to be without effect”,[70] a tenet of constitutional interpretation particularly applicable to Article I, Section 10:

In expounding the Constitution of the United States, every word must have its due force, and appropriate meaning; for it is evident from the whole instrument, that no word was unnecessarily used, or needlessly added. * * * Every word appears to have been weighed with the utmost deliberation, and its force and effect to have been fully understood. No word in the instrument, therefore, can be rejected as superfluous or unmeaning; and this principle of construction applies with peculiar force to * * * the tenth section of the first article * * * , because the whole of this short section is directed to the same subject: that is to say, it is employed altogether in enumerating the rights surrendered by the states; and this is done with so much clearness and brevity, that we cannot for a moment believe that a single superfluous word was used, or words which meant merely the same thing.[71]

Therefore, because the explicit inclusion of “the Consent of Congress” is necessary for the intervention of Congress to be allowable in cases arising under Clauses 2 and 3, then the explicit exclusion of that phrase must negate such intervention in cases arising under Clause 1, no matter under color of whichever of its powers Congress purports to act. That being so, the power “[t]o regulate Commerce” cannot possibly be construed to license Congress to prohibit the States from “making * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts”, any more than it could be construed to license Congress to compel the States “coin Money; emit Bills of Credit; [or] make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender”. For the power “[t]o regulate Commerce” “does not carry with it the right to destroy or impair those limitations and guarantees which are also placed in the Constitution”.[72] Rather, the power of Congress “[t]o regulate Commerce” and the power to the States to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender” are “fundamental principles * * * of equal dignity, and neither must be so enforced as to nullify or substantially impair the other”.[73] So, “[i]f * * * it be found that an asserted construction” of the power “[t]o regulate Commerce” “would * * * neutralize a positive prohibition of another provision of th[e Constitution], then * * * such asserted construction is erroneous, since its enforcement would mean, not to give effect to the Constitution, but to destroy a portion thereof”.[74] And, self-evidently, to “neutralize a positive [reservation]” of a State’s constitutional authority is no more justifiable than to “neutralize a positive prohibition”, particularly when the reservation at issue is itself an explicit exception to “a positive prohibition”.

(ii) Similarly, no State can ever interpose any action of Congress as purported justification for her refusal to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender” when her citizens’ economic “homeland security” demands it. On the one hand, Congress cannot compel the States to refrain from exercising any power the Constitution explicitly reserves to them. On the other hand, Congress cannot induce the States to refrain from exercising any of their reserved powers by withholding some benefit from those States that refuse to refrain. Even were that benefit legitimately within Congress’s gift, and even were it a mere “privilege” to which those States enjoyed no independent constitutional claim, its grant could not be conditioned on the States’ surrender of their rights.[75] Adherence to this limitation on Congress’s authority must be strictest when the States not only enjoy a right to exercise some reserved power but also labor under a duty to do so because the health, safety, welfare, and general prosperity of their citizens are in jeopardy.

(4) Not immediately obvious is why Article I, Section 10, Clause 1 reserves for the States the authority to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender”. After all, the selfsame clause disables the States from themselves coining any form of “Money”, including gold and silver. And Congress has a narrow authority to declare “legal tender” coextensive with its power under Article I, Section 8, Clause 5 “[t]o coin Money, [and] regulate the Value thereof”.[76] Self-evidently, if Congress coined a silver coin containing X grains of fine metal, and declared that coin “legal tender” for that precise intrinsic “Value”—then, for a State to declare such a coin “a Tender in Payment of Debts” for more, or less, than that “Value” would inject confusion and conflict into the Nation’s monetary system. Therefore, the reservation to the States of the authority to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender” cannot reasonably operate so as to contradict the parallel authority of Congress.[77]

Nonetheless, because “[i]t cannot be presumed, that any clause in the constitution is intended to be without effect”,[78] the States must be capable of exercising their reserved authority under some circumstances. Such circumstances could arise when rogue Congressmen failed, neglected, or refused to exercise Congress’s own monetary powers in a constitutional manner. For example, if Congress made no provision for domestic gold and silver coinage sufficient in quantity to meet the needs of the States and their citizens, the States could declare foreign coins, properly “regulate[d]” in “Value” as against the constitutional standard, to be “a Tender in Payment of Debts” within their respective jurisdictions.[79] Or, if Congress unconstitutionally purported to “regulate the Value” of various domestic gold or silver coins improperly with respect to the constitutional standard, in order to favor debtors, creditors, or some other politically influential special-interest group in defiance of “the general Welfare”,[80] then the States could declare those domestic coins to be “a Tender in Payment of Debts”, within their respective territorial limits, for the coins’ properly “regulate[d] * * * Value[s]”. For the power to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender” implies the power to declare at what “Value” (in terms of actual weights of precious metal) such “Coin” shall be received. Plainly, WE THE PEOPLE never delegated to Congress any power to declare “Money” to be worth more or less than its intrinsic “Value” (that is, to assign a false “Value” to coinage), nor prohibited the States from declaring the true “Value” of “gold and silver Coin” in the event of a Congressional default.[81] Or, if Congress unconstitutionally refused to “regulate the Value * * * of foreign Coin”, thereby preventing the incorporation of all such “Coin” within this country’s supply of sound “Money”, then the States could “make * * * [such foreign] gold and silver Coin a Tender” within their own jurisdictions, at appropriate “Values”.

b. Another profitable way of analyzing the question of a State’s authority to adopt an alternative currency consisting of “gold and silver Coin” recognizes that Article I, Section 10, Clause 1 constitutes not only a reservation of power to the States, but (as a result) also a limitation on the powers of the General Government.

The General Government may exercise only such powers as have been delegated to it by the Constitution. “The government of the United States is one of delegated powers alone. Its authority is defined and limited by the Constitution.”[82] “[N]o department of the government of the United States * * * possesses any power not given by the Constitution.”[83] “The government * * * of the United States can claim no powers which are not granted to it by the constitution, and the powers actually granted, must be such as are expressly given, or given by necessary implication.”[84] “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”[85] And, most importantly, “[t]he burden of establishing a delegation of power to the United States or the prohibition of power to the states is upon those making the claim”.[86]

The power to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts” is not prohibited, but is explicitly reserved, to the States. Being reserved to them, it cannot be “delegated to the United States”, such that the General Government can, directly or indirectly, prohibit or prevent the States from exercising it at their own discretion. Thus, the States’ power to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts” is effectively a limitation on the General Government.

This should not be surprising. For “the Constitution is filled with provisions that grant Congress * * * specific power to legislate in certain areas; these granted powers are always subject to the limitation that they may not be exercised in a way that violates other specific provisions of the Constitution”.[87] What needs emphasis, though, is that, “if the Constitution in its grant of powers is to be so construed that Congress shall be able to carry into full effect the powers granted, it is equally imperative that where prohibition or limitation is placed upon the power of Congress that prohibition or limitation should be enforced in its spirit and to its entirety”.[88]

(1) The only power of Congress relevant to the power of the States to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender” is Congress’s power “[t]o coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures”.[89] From this and Congress’s ancillary power “[t]o provide for the Punishment of counterfeiting the Securities and currency Coin of the United States”,[90] the conclusion is inescapable that the only official “Money” of the United States must be “Coin”. That being so, no inherent conflict can possibly exist between Congress’s monetary authority and the power of the States to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender”, provided that both Congress and the States properly “regulate the Value[s]” of the “Coin” they declare to be “legal tender”.

A conflict could arise if rogue Congressmen purported, under color of the power “[t] coin Money, [and] regulate the Value thereof”, to enact a statute that somehow prohibited the States from “mak[ing] * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender”.[91] The proponents of such a statute would doubtlessly invoke in its behalf the Constitution’s so- called “Supremacy Clause”, which provides that “the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance [of the Constitution] * * * shall be the supreme Law of the Land * * * , any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding”.[92] The patent fallacy in their reasoning, though, would be that the “supreme” status of any “Law[ ] of the United States” is as against “any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary”, not as against prohibitions or reservations of power within the Constitution itself.[93] As should be logically as well as legally self-evident, Congress cannot enact any purported “Laws” supposedly “in Pursuance [of the Constitution]” that themselves contradict the Constitution.

Moreover, if the monetary powers of Congress could override the reservation of State authority in Article I, Section 10, Clause 1, simply because the Constitution confers those powers on Congress, no need would exist for the explicit qualification in Clauses 2 and 3 that allows the States to take various actions only with “the Consent of Congress”. For the actions those clauses conditionally allow also come within certain of the power of Congress—such as to “lay any Imposts or Duties on Imports”,[94] “keep Troops, or Ships of War in time of Peace”,[95] or “engage in War”.[96] But, to construe this condition as supererogatory would violate perhaps the most basic canon of constitutional interpretation.[97]

(2) If the monetary powers of Congress and the power of the States to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender” are properly construed, no chance of any conflict between the two will ever arise. This is primarily because, even if the “gold and silver Coin” that any State “ma[d]e * * * a Tender” were different from the “legal tender” authorized by Congress, it would function as merely an alternative currency, which the State and her citizens could freely choose to employ in their monetary transactions or not. That they are free to do as much right now pursuant to a Congressional statute[98] proves that no conflict would arise simply because they might justify their action on the basis of the Constitution rather than a statute.

(a) As to coinage. Obviously, the power actually “[t]o coin Money” is the exclusive prerogative of Congress, because the Constitution explicitly delegates that power to Congress and explicitly withholds it from the States.[99] But for the States to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender” does not require that the States themselves “coin Money”, only that they designate as “a Tender” “gold and silver Coin” coined by someone else.

(b) As to paper currency. “Bills of Credit” was the Framers’ term for “paper currency”, which at that time was usually supposed to be redeemable in gold or silver coin. Article I, Section 10, Clause 1 absolutely disables the States from “emit[ting] Bills of

Credit”. And, quite correctly, the Supreme Court has ruled that the States may not emit “Bills of Credit” under any other designation or label.[100] But a power in the States to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender” could never involve the States in the emission of “Bills of Credit”—as Article I, Section 10, Clause 1 itself recognizes, by prohibiting the States from “emit[ting] Bills” while allowing them to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender”.

Although its evolution from the Articles of Confederation, through the Federal Convention of 1787, proves beyond any doubt that the Constitution actually withholds from Congress the power to “emit bills”,[101] the Supreme Court has erroneously ruled (doubtlessly for political reasons) that Congress, under color of its power “[t]o borrow Money on the credit of the United States”, may emit “securities” in the form of Treasury Notes intended and suited to circulate as a paper currency with the status of “legal tender”.[102] On this basis, contemporary Federal Reserve Notes amount to similar “securities”, because such notes are evidences of “advances” made by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System to Federal Reserve regional banks, constitute “a first and paramount lien on all the assets of such bank[s]”, and “shall be obligations of the United States”;[103] and have been declared to be “legal tender for all debts, public charges, taxes, and dues”.[104] Yet, although all “United States money is expressed in dollars”,[105] Federal Reserve Notes are not themselves “dollars”, but only promises to pay “dollars”.[106] Moreover, unlike United States Treasury Notes of the type first issued during the Civil War,[107] Federal Reserve Notes are not themselves “lawful money”, either, because the statute authorizing their emission also provides that “[t]hey shall be redeemed in lawful money on demand on the Treasury Department of the United States * * * or at any Federal Reserve bank”[108]—and, self-evidently, if all Federal Reserve Notes must be “redeemed in lawful money”, then one Federal Reserve Note cannot “redeem[ ]” another, and therefore no Federal Reserve Note can be taken to be “lawful money”.

By “mak[ing] * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender”, a State will not interfere with anyone who freely chooses to use Federal Reserve Notes as a medium of exchange, because (assuming for purposes of argument the constitutionality of the Federal Reserve System and Federal Reserve Notes) the right to do so is secured by “the Laws of the United States”.[109] Also, “mak[ing] * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender” for purposes of State law cannot interfere with the redemption of Federal Reserve Notes under “the Laws of the United States”, because under those “Laws” (again, assuming their constitutionality) redemption of Federal Reserve Notes in gold or silver coins cannot be had in any event.[110]

(c) As to “legal tender”. The question of “legal tender” breaks down into two categories: namely, “legal tender” as applied to various types of coinage, and “legal tender” as applied to paper currency.

(i) Presumably, every gold and silver coin that Congress orders to be minted ought to be “legal tender” for its face “Value”, if Congress has properly “regulate[d] th[at] Value”.[111] And Congress has imbued all of the gold and silver coinage minted by the Treasury of the United States with the status of “legal tender”.[112] Self-evidently, for States to “make * * * [all of this domestic] gold and silver Coin a Tender” under their own laws could not interfere with, but would merely confirm and reinforce the effect of, Congress’s equivalent designation.

(ii) Distinguishably, pursuant to its power to “regulate the Value * * * of foreign Coin”, Congress could—and should—declare all such gold and silver “Coin” to be “legal tender”, too.[113] But it has chosen not to do so at the present time: “Foreign gold and silver coins are not legal tender for debts.”[114] This flies in the face of Article I, Section 8, Clause 5, because the power “regulate the Value * * * of foreign Coin” aims at incorporating “foreign Coin” into America’s monetary system to the greatest degree practicable, not excluding it altogether. Nonetheless, the most that this injunction could possibly prohibit is the use of “[f]oreign gold or silver coins” as “legal tender for debts” under “the Laws of the United States”. For, constitutionally, it cannot apply to situations governed by the laws of the States. Every statute of Congress, after all, is subject to the limitation that “[t]h[e] Constitution * * * shall be the supreme Law of the Land”.[115] The Constitution recognizes the authority of the States to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts”, without any exception as to the source of the “Coin”. Therefore, the Constitution prohibits Congress from purporting by statute to exclude “[f]oreign gold or silver coins” from the ambit of the States’ authority. Thus, the statute in issue would have to be read as providing that “[f]oreign gold and silver coins are not legal tender for debts except where a State has designated them as such”.

Nothing particularly radical lurks in such an exception, either. For to declare any foreign gold or silver “Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts” is merely to mandate that it shall be accepted for its actual weight in pure gold or pure silver when a contract stipulates payment in coin in one of those metals. It does not require that such a coin be accepted in payment when a contract stipulates that some other medium of exchange be employed for that purpose.

(iii) Furthermore, Congress has ordered the Treasury to strike base-metallic coins, and has declared them to be “legal tender” for their face values in nominal “dollars”.[116] Once again, though, even if a State “make[s] * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender” under her own laws, anyone may, simply by exercising due care in drafting a contract, choose to employ United States base-metallic coins as “legal tender”, in preference to and even exclusion of any gold or silver coins.[117]

Thus, with respect to all coinage, what will be the actual “legal tender” for a particular transaction will always depend in the final analysis upon the intent of the parties, not upon the abstract designation as “legal tender” that some statute happens to fix for a particular coin. For example, Congress has declared United States “American Eagle” gold coins and “Liberty” silver coins to be “legal tender”.[118] Nevertheless, Congress requires no one to employ them as such, in preference to, let alone to the exclusion of, any other coin or currency.[119] And presumably no one would ever pay with “legal-tender” gold or silver coins a debt which could be paid, “dollar for dollar”, with “legal-tender” base- metallic coins instead. Similarly, if a State “ma[d]e * * * [American Eagle and Liberty] gold and silver Coin a Tender”, she could not require anyone within her private economy to employ those coins as “legal tender” in their day-to-day transactions.[120] A State could, of course, require any person dealing with her own government to use “gold and silver Coin [as] a Tender”—but, in the simplest terms, that would simply reflect the State’s taking advantage of a statutory right available to all under “the Laws of the United States”.[121]

(iv) Finally, Congress has declared Federal Reserve Notes to be “legal tender for all debts, public charges, taxes, and dues”.[122] Nonetheless, as with all other forms of currency, Federal Reserve Notes are not “legal tender” when a contract explicitly specifies that something else will be the only medium of payment acceptable to the parties.[123] Then that something else is the only “legal tender” for that contract. On the other hand, notwithstanding that Congress has designated some gold and silver coins to be “legal tender”, and even if the States “ma[d]e * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender”, under the present “Laws of the United States” anyone could, by properly drafting his monetary contracts, refuse to accept as a medium of payment anything but Federal Reserve Notes.[124] Precisely why any rational person would take such action in practice is perhaps beyond explanation. But that everyone has the legal right in principle to do so is beyond doubt.

c. If any of the non-monetary powers of Congress were misconstrued to override the States’ authority under Article I, Section 10, Clause 1, they would impermissibly conflict with Congress’s own monetary power, as well as with the States’.

Congress’s only explicit monetary power is the power “[t]o coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin”.[125] This clause both explicitly defines—and by that unique definition limits—Congress’s authority with respect to “Money”, excluding all other powers in that regard. For “[a]ffirmative words are often, in their operation, negative of other objects than those affirmed”.[126] So, just as the other powers of Congress may not be construed so as to detract from its power “[t]o coin Money”, no other powers may be construed so as to add to that power, extending it beyond its terms. For all of Congress’s constitutional powers are of “equal dignity”, and therefore none “must be so enforced as to nullify or substantially impair [any] other”.[127]

In particular, Congress’s power “[t]o regulate Commerce”[128] “does not carry with it the right to destroy or impair those limitations and guarantees which are also placed in the Constitution”.[129] It is, of course, easy enough to concoct a chain of spurious reasoning in support of the notion that the power “[t]o regulate Commerce” enables Congress to override the States’ authority to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender” under Article I, Section 10, Clause 1. For example, that—(i) Congress cannot “regulate Commerce” until there is “Commerce”; (ii) in a market economy, “Commerce” cannot function without prices of goods and services; (iii) prices cannot exist without money; therefore (iv) in order to “regulate Commerce”, Congress must exercise a power to create money, so as to generate prices and thereby facilitate “Commerce” subject to “regulat[ion]”; and (v) because the power “[t]o regulate Commerce” in not limited in that regard, Congress may create and designate as “legal tender” whatever it wants as money; and, as a result, (vi) because Congress’s authority is “supreme”, it can prohibit anyone else from creating any other money or designating anything else as “legal tender”. The obvious fallacy here, though, is that, were this reasoning cogent, then the power “[t]o regulate Commerce” would be a “monetary power” far broader than the actual monetary power the Constitution delegates to Congress. In which case, the monetary power the Constitution explicitly recites would be, not only superfluous, but no less than a fraudulent statement of Congress’s authority. But no provision of the Constitution is superfluous.[130] And certainly no provision of the Constitution can be so misinterpreted as to perpetrate a fraud on the face of that document. Therefore, the power “[t]o regulate Commerce” cannot override the State’s authority in Article I, Section 10, Clause 1 because that power cannot expand Congress’s power in Article I, Section 8, Clause 5, which must itself be construed in harmony with Article I, Section 10, Clause 1.

d. In practice, a State could exercise her authority under Article I, Section 10, Clause 1 to “make * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts”, and render such an alternative currency economically and politically viable, by:

• listing various domestic and foreign gold and silver coins—properly valued against the constitutional standard according to their actual contents of fine metal—as suitable for “Tender in Payment of Debts”;

• declaring that only those coins would be employed in certain (perhaps, eventually, all) financial transactions or other payments in the nature of “Debts” that involved the State, her subdivisions, and their employees, agents, and contractors;[131]

• recognizing that anyone else in the State who chose not to employ “gold and silver Coin [as] a Tender” could enter into contracts both payable in whatever other currency the parties agreed to use, and specifically enforceable in those terms in the State’s courts;[132] and

• facilitating the use of “gold and silver Coin [as] a Tender” by inter alia

(i) creating a State depository which would establish and manage accounts in coin for the State and her citizens, transfer ownership of gold and silver among these accounts by such means as electronic assignments, debit-cards, and checks, and maintain appropriate accounting records for depositors;

(ii) providing businessmen in the State with the necessary computer-software and instructions to enable them to price their goods and services in terms of gold and silver on a day-to-day basis;

(iii) offering incentives to businessmen to encourage, or even to require, their customers to employ “gold and silver Coin [as] a Tender” in dealing with their businesses;

(iv) simplifying the calculation and collection of State and Local business taxes by allowing (for example) transactions effected in gold and silver to be valued, and taxes on or related to those transactions to be paid, in gold and silver; and

(v) collecting various minor but general taxes, fees, and other public charges in “gold and silver Coin” as soon as practicable, so as to familiarize as many citizens as possible with the existence and operation of the alternative currency system. As individuals are required to pay an increasing number of their taxes, fees, and other public charges in gold and silver, they will inevitably—and probably quite quickly—begin to ensure that their own incomes are also paid in gold and silver to some significant degree, thus rapidly expanding the use of the alternative currency throughout the private sector.

2. The States’ power to adopt an alternative currency consisting of gold and silver in a form other than coin.

An economically sound, constitutional, and honest alternative currency consisting of gold and silver need not employ those metals only in the form of “Coin”. For nothing in the Constitution prohibits a State from adopting any alternative currency, as long as, in so doing, the State herself does not “coin Money; emit Bills of Credit; [or] make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts”.[133]

a. From a technological perspective, probably the best alternative currency available today is so-called “electronic gold currency” and “electronic silver currency”. Here, “electronic” refers to the method for recording and transferring legal title to specific amounts of gold or silver bullion actually held by an “electronic currency provider” in special “bailment” accounts for depositors’ use as currency.[134] “Electronic gold currency” and “electronic silver currency” offer numerous advantages over gold and silver coins deposited in typical banks. Foremost among these are:

• Security: The gold and silver on deposit are owned by the depositors themselves and not by the “electronic currency providers” that hold those deposits. The depositors are “bailors” of the specie, the “providers” “bailees”. With a typical bank, conversely, a deposit becomes the property of the bank, with the depositor merely a general creditor of the bank for the value of his deposit.

• Ubiquity: Anyone maintaining an account with an “electronic currency provider” can easily acquire gold and silver through the “provider” and then deal with anyone else holding such an account, anywhere in the world.

• Convenience: transactions in gold and silver can be effected with debit-cards or like instruments, so that payment of gold or silver is had immediately; but the actual specie never has to leave the “electronic currency providers’” vaults. Of course, transactions also can be effected on the basis of paper receipts in the nature of checks, or actual physical delivery of gold or silver, if the parties so desire

• Flexibility: Transactions of very small and exact values can be made, which is impossible with coins. And

• Accuracy: The details of every transaction can be automatically recorded for purposes of accounting, including inter alia the date; the time; the parties to the transaction; the location of the transaction; the nature and purpose of the transaction; and the value of the transaction in gold, silver, Federal Reserve Notes, or any other common medium of exchange.

To put such a system into practice, a State would establish within her government an official “electronic gold and silver currency provider”.[135] The constitutionally as well as politically most secure arrangement would be to staff this agency with properly trained members of the State’s Militia, and to secure the gold and silver bullion in a depository under the Militia’s direct supervision, operation, and physical control.[136] This would provide the inestimable advantage of maintaining actual possession of the people’s gold and silver in the people’s own hands at all times. Particular depositors’ gold and silver would be held in separate bailment accounts, so that the system could not be accused of operating on the basis of unconstitutional “electronic ‘Bills of Credit’”, or economically unsound “fractional reserves”.[137] Yet the depositors’ gold and silver would always be impressed with the attributes of the State’s sovereign power, because the State had designated that gold and silver as her alternative currency.[138] Thus, the gold and silver in the State’s depository would be serving, not only the particular purposes of the various depositors, both public and private, but also the overarching public purpose of guaranteeing the State’s economic “homeland security”. Consequently, not only the gold and silver deposited by the State herself and all of the governmental bodies and agencies within her jurisdiction, but also the specie deposited by members of her Militia in their capacities and pursuant to their duties as such—which would include the vast majority of her population—would be protected by a governmental immunity from any form of interference on the part of rogue agents of the General Government. Arguably, this immunity would extend to the silver and gold used as media of exchange by every one of the State’s citizens, whether members of her Militia or not, because all such use would be in aid of preserving the State’s economic “homeland security”.

b. For constitutional purposes, the distinction between an “electronic gold currency” or “electronic silver currency” consisting of gold or silver bullion, on the one hand, and actual gold or silver “Coin”, on the other, is small in practice and inconsequential in principle.

Instructive in this regard is the Supreme Court’s decision in Bronson v. Rodes.[139] At issue was whether a private contractual obligation of “dollars payable in gold and silver coin, lawful money of the United States” was, notwithstanding that stipulation, payable in United States Treasury Notes which Congress had declared to be “legal tender” but were not redeemable in either gold or silver. In order to determine “the precise import in law” of the key contractual phrase, the Court reviewed the Coinage Acts of Congress from 1792 onwards, observing that “[t]he design of all this minuteness and strictness in the regulation of coinage * * * recognizes the fact, accepted by all men throughout the world, that value is inherent in the precious metals; that gold and silver are in themselves values, and being such * * * are the only proper measure of value; that these values are determined by weight and purity”—and that “[e]very * * * dollar is a piece of gold or silver, certified to be of a certain weight and purity, by the form and impress given to it at the mint * * * and therefore declared to be legal tender in payments”.[140] From all this, the Court concluded that

[a] contract to pay a certain number of dollars in gold or silver coins is, therefore, in legal import, nothing else than an agreement to deliver a certain weight of standard gold, to be ascertained by a count of coins, each of which is certified to contain a definite proportion of that weight. It is not distinguishable * * * , in principle, from a contract to deliver an equal weight of bullion of equal fineness. It is distinguishable, in circumstance, only by the fact that the sufficiency of the amount to be tendered in payment must be ascertained, in the case of bullion, by assay and the scales, while in the case of coin it may be ascertained by count.[141]

Thus, “mak[ing] * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender” should not be distinguishable in constitutional principle from “mak[ing] * * * [an equal weight of bullion of equal fineness] a Tender”. The only concern should be how to assure in practice that, in either case, an “equal weight” of metal of the same fineness is delivered. This will depend, however, upon how “equal weight” is defined—whether physically or economically.

Traditionally, a coin containing a certain weight of pure gold or silver has been considered to be of somewhat greater market value than—that is, has commanded a “premium” over—gold or silver bullion of the same weight. This, because each coin is so designed as to certify its source, substance, content, and in most cases nominal legal value as “money”, and therefore on its face imparts more information than an equal physical weight of mere bullion. Also, coins are fabricated in sizes deemed convenient for commerce, and with a small amount of base metal added to the gold or silver, in order to harden the resulting alloy so as to facilitate its use in hand-to-hand transactions—and therefore are more useful than bullion in that context. Such design and fabrication add economic value to the bullion a coin contains.[142]

Traditionally, too, the Treasury has minted gold and silver coins according to the principle of “free coinage”, whereby an individual who brought some weight of gold or silver bullion to the Mint would receive, after a time, coins containing the selfsame weight of metal, struck at no charge to him; or, if he preferred immediate receipt (and the Mint concurred), could accept coins containing some lesser weight according to a fixed formula. For example, the first Coinage Act enacted under the Constitution provided that “any person” might

bring to the * * * mint gold and silver bullion, in order to their being coined; and * * * the bullion so brought shall be * * * coined as speedily as may be after the receipt thereof, and that free of expense to the person * * * by whom the same shall have been brought. And as soon as the said bullion shall have been coined, the person * * * by whom the same shall have been delivered, shall upon demand receive in lieu thereof coins of the same species of bullion which shall have been so delivered, weight for weight, of the pure gold or pure silver therein contained: Provided, nevertheless, That it shall be at the mutual option of the party * * * bringing such bullion, and of the director of the * * * mint, to make an immediate exchange of coins for standard bullion, with a deduction of one half per cent. from the weight of the pure gold, or pure silver contained in the said bullion, as an indemnification to the mint for the time which will necessarily be required for coining the said bullion, and for the advance which shall have been so made in coins.[143]

This, because the conversion of bullion into coinage has always been considered a prerogative of sovereignty that performs a indispensable public function,[144] and therefore the cost of which is rightfully chargeable to the public, unless some special benefit is to be provided to the purveyor of the bullion, in which case any excess charge that has to be incurred may fairly be laid upon him.

It would appear from this early practice that the principle of “free coinage”, with its implicit recognition of the “premium” between coinage and bullion, and its allocation of the cost of generating new coinage to the public in the first instance, constitutes an integral part of Congress’s power “[t]o coin Money”,[145] and therefore must be taken into consideration if a State chooses to employ bullion as an alternative currency in preference to or even conjunction with “Coin”, so that nothing the State does in the course of “mak[ing] * * * gold and silver Coin a Tender” conflicts with that power.[146]