Last Updated on January 16, 2023 by Constitutional Militia

Decisions of Courts Have No Rank as “Law”

“[i]n the ordinary use of language it will hardly be contended that the decisions of Courts constitute laws. They are, at most, only evidence of what the laws are; and are not of themselves laws. They are often re-examined, reversed, and qualified by the Courts themselves, whenever they are found to be either defective, or ill-founded, or otherwise incorrect.”

Source: Swift v. Tyson, 41 U.S. (16 Peters) 1, 18 (1842). “I understand the doctrine to be in such cases [i.e., cases in which a court overrules a previous decision], not that the law is changed, but that it was always the same as expounded by the later decision, and that the former decision was not, and never had been, the law, and is overruled for that very purpose.” Gelpcke v. City of Dubuque, 68 U.S. (1 Wallace) 175, 211 (1864) (Miller, J., dissenting).

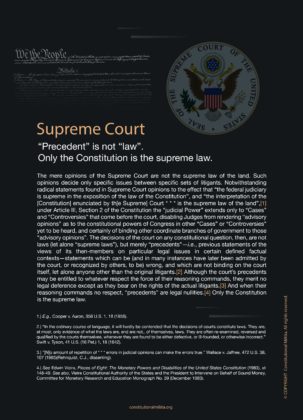

Misconstrued Role of the Supreme Court as “Ultimate Interpreter” of the United States Constitution.

Certainly, Americans were not so childish in the pre-constitutional period—and should not be so silly today—as to need or to seek tutelage in their constitutional political science from the very public officials whom they themselves had or have selected, particularly judges. For, as William Blackstone the Founding Fathers’ preëminent legal mentor pointed out, “the law, and the opinion of the judge are not always convertible terms, or one and the same thing; since it sometimes may happen that the judge may mistake the law”.[1] Neither should Americans today kowtow to judges or other public officials with regard to constitutional interpretation, especially in light of the Supreme Court’s own admissions of its numerous errors in that field over the years and reversed itself numerous times on constitutional questions.[2]

The Supreme Court’s decisions are no more than previous statements of the views of its then-members on particular legal issues raised by particular litigants in certain specifically defined factual contexts—statements which can be (and in many instances have later been admitted by the Court itself, or recognized by others, to be) wrong, and which are not binding on the Court itself, let alone on anyone other than the original litigants, especially where constitutional issues are concerned.[3] So, although these decisions may be entitled to whatever respect the force of their reasoning commands, they merit no legal, logical, or factual deference except insofar as they bear on the rights of the actual litigants in a “Case[ ]” or “Controvers[y]”.[4] And when their reasoning commands no respect, these decisions must be dismissed as legal nullities, except as against the actual litigants themselves. For “no amount of repetition of * * * errors in judicial opinions can make the errors true”.[5]

No constitutional Republic could long survive if the country is required to take the gut reaction of judges as to its final guide—so that as most decisions of the Supreme Court (if not all courts) today, “the governing standard is *** what might be called the unfettered wisdom of a majority of th[e judges] , revealed to an obedient people on a case-by-case basis. This is not only not the government of laws the Constitution established; it is not a government of laws at all.”[6]

Nowhere in the Constitution are judges granted “life tenure”. On the contrary, the Constitution recognizes that any sitting judge can be removed if an aberrant course of unconstitutional decision making fails to meet the standard of “good Behaviour”.[7]

Court’s decisions are not conclusive, inasmuch as the Supreme Court itself has admitted error and reversed itself numerous times on constitutional questions.[8]

The idea that decisions of courts are laws, at all in the sense of constitutional provisions and statutes are, came into vogue only after publication of Grey’s “The Nature and Sources of Law”, in 1909.[9]