Last Updated on August 20, 2022 by Constitutional Militia

Justice Joseph Story

Story’s Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States are recognized as a standard work in constitutional law. See, e.g., Field v. Clark, 143 U.S. 649, 670-71 (1892).

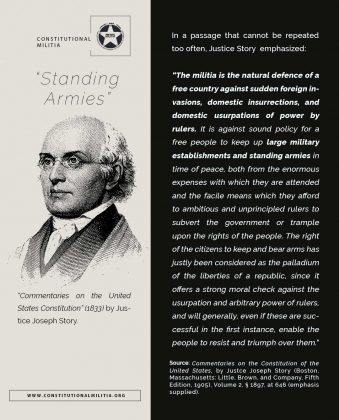

Justice Joseph Story : “Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States”

Justice Joseph Story was a member of the Supreme Court during the time of John Marshall in the early 1800′s. He wrote a book called, “Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States”, which is a textbook analyzing the United States Constitution. Constitutional law in that era, was taught from textbooks. Law professors would go through the Constitution, line by line, clause by clause, explaining the meanings and give some analysis relating to the debates among the Founding Fathers and the history of the Colonies. Justice Story’s Commentaries, along with Sir William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England were among the best known and widely regarded works for understanding the United States Constitution. Yet no law schools today use these books.

“[T]he Militia of the several States” are the constitutional institutions which, properly organized, would secure WE THE PEOPLE’S “right to keep and bear Arms” and maximize its political significance and practical efficacy. Yet next to no Americans know anything about them today. The main sources of this problem are two: first, the general antinomian notion that the Constitution is merely a set of “legal technicalities”, many of them stodgily anachronistic, which can be disregarded whenever what passes for more modern political policy counsels the convenience of doing so; and second, the specific concern Joseph Story long ago pinpointed, that selfish individuals would desire to be dispensed from personal service in the Militia whenever they had no reason to fear the consequences—what he recognized even in the early 1830s:

“The importance of a well-regulated militia would seem so undeniable, it cannot be disguised that, among the American people, there is a growing indifference to any system of militia discipline, and a strong disposition, from a sense of its burdens, to be rid of all regulations. How it is practicable to keep the people duly armed without some organization it is difficult to see. There is certainly no small danger that indifference may lead to disgust, and disgust to contempt; and thus gradually undermine all the protection intended by th[e Second Amendment] of our national bill of rights.”[1]

Ignorance to the Militia today gains an invaluable prop from both sides of the individual “gun rights” debate who disregard entirely what the Second Amendment itself declares “necessary to the security of a free State”—“A well regulated Militia”—the source of average American’s governmental legal authority to provide themselves with “the security of a free State” from any and all threats—the worse being rogue government officials who break the law under color of “law”.

Large centralized, bureaucratic, and professional police, domestic-security, and intelligence establishments—especially those that can exert their authority by force of arms in one State or locality with personnel drawn from other States and Localities—should not be kept up either, because they, too, perhaps to a degree even greater than “large military establishments and standing armies”, provide a “facile means * * * to ambitious and unprincipled rulers to subvert the government or trample upon the rights of the people”. The history of the Twentieth Century emphatically teaches that such police, domestic-security, and intelligence establishments inevitably tend—if they are are not always intended from their inceptions—to serve the special interests of self-perpetuating political-cum-economic élitists at common people’s expense. Thus, they are always at least potential instruments for tyranny. Militia, conversely, provide a people with forces for deterrence—and where that fails, defense—and where that fails, resistance.[2]