Last Updated on January 15, 2023 by Constitutional Militia

“To * * * regulate * * * Value ” and the cognate power “To * * * fix the standard of Weights and Measures”

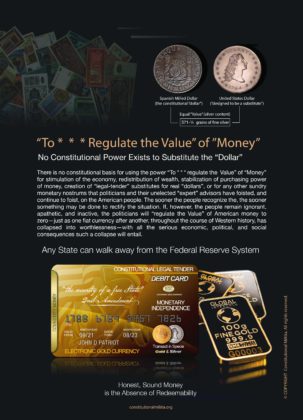

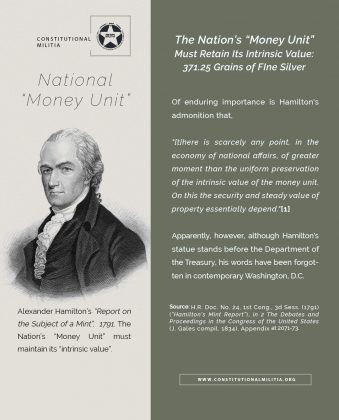

The phrase “fix the standard” empowers Congress itself to define the basic units of “Weights and Measures”; whereas the phrase “regulate the Value” empowers Congress only to apply the basic unit of “Value”, which the Constitution elsewhere explicitly identifies as the “dollar[ ]”, a known historically fixed weight of silver beyond Congress’s power to change.[1]

Congress’s Power “To * * * regulate * * * Value”

As with the power “To coin Money”, the allied power in Article I, Section 8, Clause 5 “To * * * regulate the value, and of foreign Coin” traces its ancestry to linguistically similar—and operatively identical language in the Articles of Confederation, later successfully modified in the Federal Convention of 1787.[2] Of no little significance is the Framers’ consistent association throughout its evolution, of the power “To * * * regulate * * * Value ” with the cognate power “To * * * fix the standard of Weights and Measures” which also appears in Clause 5.[3] Again, as with the power “To coin”, nowhere in the Constitution or anywhere antecedents does or did another explicit power exist to “regulate the Value” of “currency”, “bills of credit”, “securities”, “notes”, “paper money”, or anything other than United States and foreign coin. The verb “regulate” refers to a particular, specific activity relating only to coinage rather than “granting general powers of legislation” to declare what shall have “Value”, and to what degree, as “Money”.[4]

This is not because the Founding Fathers were economic illiterates, unconversant with what some people may flatter themselves are modern ideas about managed paper currencies. To the contrary: From their own experiences and their knowledge of Colonial history, they were well aware that legislatures and courts had often attempted to manage paper money, by setting rates of exchange for “bills of credit”, and revaluing (“scaling”) contracts expressed in paper money, using tabular standards and like devices.[5] Because they also knew that the choice of which standards to use in these essays in monetary (mis)management easily degenerated into a political contest, they must have been concerned that, were any such power included in the Constitution, it should be specified clearly.[6] So, if they included no congressional power “To * * * regulate the Value” applicable to “bills of credit”, it must be because they deemed it unnecessary—which, of course it would be if Congress, both under Article I, Section 8, Clause 2,[7] and the States under Article I, Section 10, Clause 1,[8] lacked all power to emit “bills of credit” , and therefore needed no power “To * * * regulate the Value thereof”. That is, in the historical context of the Founders’ experiences with managed paper currencies, the absence of an explicit power “To * * * regulate the Value of Bills of Credit” is compelling evidence that the Constitution contains no implicit power for government at any level to emit “bills of credit” .

The specificity for coin of the power “To * * * regulate the Value thereof and of foreign Coin” unequivocally define’s that powers substance. “[R]egulate” meant then,[9] as it does today[10] to adjust according to some rule or standard. “‘The word ordinarily implies not so much the creating or establishment of a new thing, as the arranging in proper order and controlling that which already exists.’”[11] Such an “arranging in proper order” succinctly describes what “regulat[ing]” coinage meant, in governmental practice and public understanding, prior to the ratification of the Constitution.