Last Updated on March 16, 2022 by Constitutional Militia

Militia: Unconstitutionally Disestablished and Fused with the Regular Armed Forces

Militia had been in existence for generations throughout America, settled and regulated pursuant to Colonial and then State statutes. And there are hundreds of Militia statutes that go back to the early 1600′s, until after the Constitution, as they kept passing them pursuant to constitutional authority. Militia, as a matter of fact and law were governmental structures, thoroughly civilian in character, separate and distinct from the regular armed forces—often referred to and denounced by Founding Patriots as “standing armies”. Indeed, the Founding Fathers were all to familiar with “martial law” that was part and parcel of “standing armies” in the American colonies, which the Declaration of Independence identified as one of the most egregious forms of “an absolute Tyranny” freighted upon “the good People of these Colonies”.

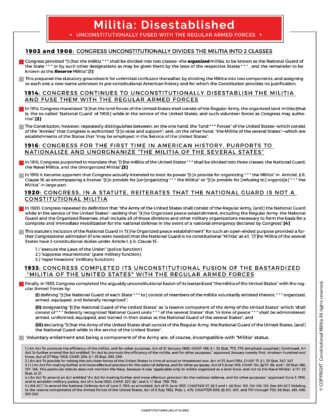

Unfortunately, even with all of this information before it, in the early Twentieth Century Congress began thoroughly to muddle the constitutional differentiation between the “the Militia of the several States” and the regular Armed Forces:

• In 1903 and 1908, Congress provided “[t]hat the militia * * * shall be divided into two classes—the organized militia, to be known as the National Guard of the State * * * or by such other designations as may be given them by the laws of the respective States * * * , and the remainder to be known as the Reserve Militia”.[1] This prepared the statutory groundwork for unlimited confusion thereafter, by bifurcating the Militia into two components, and assigning to each one a new name unknown in pre-constitutional American history and for which the Constitution provides no justification.

In 1914, Congress mandated “[t]hat the land forces of the United States shall consist of the Regular Army, the organized land militia [that is, the so-called ‘National Guard’ of 1908] while in the service of the United States, and such volunteer forces as Congress may authorize”.[1] The Constitution, however, repeatedly distinguishes between, on the one hand, the “land * * * Forces” of the United States—which consist of the “Armies” that Congress is authorized “[t]o raise and support”; and, on the other hand, “the Militia of the several States”—which are establishments of the States that “may be employed in the Service of the United States”. And it does so in a manner that absolutely precludes the conflation of the two different types of establishments.[2] For example, that “the Militia of the several States” can be “employed in the Service of the United States” or not, and that the President can be the “Commander in Chief * * * of the Militia of the several States” or not, depending upon circumstances that lie beyond Congress’s and the President’s control, proves that the Militia can not be “forces of the United States”—otherwise they would always be “in the Service of the United States”, and always under the President’s control as “Commander in Chief”, just as are the regular Armed Forces.[3] And that the Constitution delegates to Congress the separate and distinct powers “[t]o make Rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval Forces”[4] and “[t]o provide for * * * governing such Part of the[ Militia] as may be employed in the Service of the United States”[5] establishes beyond peradventure that “such Part of the[ Militia] as may be employed in the Service of the United States” can never become part of “the land forces of the United States”, or else two different powers for governing them, purportedly as such, would not be necessary—and “[i]t cannot be presumed that any clause in the constitution is intended to be without effect”.[6]

Footnotes:

1.) An Act To provide for raising the volunteer forces of the United States in time of actual or threatened war, Act of 25 April 1914, CHAP. 71, § 1, 38 Stat. 347, 347.

2.) Compare and contrast U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cls. 12 through 14 with art. I, § 8, cls. 15 and 16, with art. II, § 2, cl. 1, and with amend. V.

3.) See U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cls. 15 and 16, and art. II, § 2, cl. 1.

4.) U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 14.

5.) U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 16.

6.) Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137, 174 (1803).

In 1916, Congress purported to mandate that “[t]he militia of the United States * * * shall be divided into three classes, the National Guard, the Naval Militia, and the Unorganized Militia”; “[t]he National Guard shall consist of the regularly enlisted militia * * * organized, armed, and equipped”; and “the Army of the United States shall consist of the Regular Army, the Volunteer Army, * * * the National Guard while in the service of the United States, and such other land forces as are now or may hereafter be authorized by law”.[1] Here, for the first time in American history, Congress set up an explicit dichotomy between an “organized” and an “unorganized” “militia”—because, from 1903 to 1916, it might have been possible to imagine that, although the National Guard was described as “the organized militia”, nonetheless the so-called “Reserve Militia” was also to be in some manner “organized”. In 1916, however, it became apparent that Congress actually intended to treat its power “[t]o provide for organizing * * * the Militia”[2] as encompassing a license “[t]o provide for [un]organizing * * * the Militia” or “[t]o provide for [refusing to] organiz[e] * * * the Militia” in large part. In addition, also for the first time in American history, Congress purported to transmogrify the separate “Militia of the several States” (in the plural) into the constitutionally impossible unified “militia of the United States” (in the singular), notwithstanding that Congress’s only authority in the premises is “[t]o provide * * * for governing such Part of them as may be employed in the Service of the United States”;[3] and notwithstanding that the Constitution designates the President as “Commander in Chief * * * of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States”—not “the Commander in Chief * * * of the Militia of the United States”, even when “the Militia of the several States” have been “called into the actual Service of the United States”.[4] Worse yet, Congress purported under some circumstances to absorb “the militia of the United States” into “the Army of the United States”, notwithstanding (as will be explained immediately below) that the Constitution requires the Militia and the Army to be separate and distinct establishments precisely so that the Militia may act as independent “checks and balances” against rogue elements in the Armed Forces.[5]

Footnotes:

1.) An Act For making further and more effectual provision for the national defense, and for other purposes, Act of 3 June 1916, CHAP. 134, §§ 57, 58, and 1, 39 Stat. 166, 197, 166. This particular statute does not mention the Navy, because it was “applicable only to militia organized as a land force, and not to the Naval Militia”. § 117, 39 Stat. at 212.

2.) 2.) U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 16.

3.) U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 16 (emphasis supplied).

4.) U.S. Const. art. II, § 2, cl. 1.

5.) The Sword and Sovereignty: The Constitutional Principles of “the Militia of the several States”, Front Royal, Virginia CD ROM Edition 2012, by Dr. Edwin Vieira, Jr., page 788.

In 1920, Congress repeated its definition that “the Army of the United States shall consist of the Regular Army, [and] the National Guard while in the service of the United States”—adding that “[t]he Organized peace establishment, including the Regular Army, the National Guard and the Organized Reserves, shall include all of those divisions and other military organizations necessary to form the basis for a complete and immediate mobilization for the national defense in the event of a national emergency declared by Congress”.[1] Self-evidently, if “a national emergency declared by Congress” arose under circumstances that did not require “[para-military] execut[ion of] the Laws of the Union, suppress[ion of] Insurrections and repel[ling of] Invasions”—as many such purported “emergencies” have over the years, and as the very generality of the term “emergency” suggests—then “the Militia of the several States” could not constitutionally be “call[ed] forth” into “the Service of the United States” at all.[2] So, this statute’s inclusion of the National Guard in “[t]he Organized peace establishment” for such an open-ended purpose provided a further Congressional admission (if one were needed) that the National Guard is no constitutional “Militia” at all.[3]

Footnotes:

1.) An Act To amend an Act entitled “An Act for making further and more effectual provision for the national defense, and for other purposes,” approved June 3, 1916, and to establish military justice, Act of 4 June 1920, CHAP. 227, §§ 1 and 3, 41 Stat. 759, 759.

2.) See U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cls. 15 and 16, and art. II, § 2, cl. 1.

3.) The Sword and Sovereignty: The Constitutional Principles of “the Militia of the several States”, Front Royal, Virginia CD ROM Edition 2012, by Dr. Edwin Vieira, Jr., page 788.

Finally, in 1933, Congress completed the arguably unconstitutional fusion of its bastardized “militia of the United States” with the regular Armed Forces by:

(i) defining “[t]he National Guard of each State * * * to] consist of members of the militia voluntarily enlisted therein, * * * organized, armed, equipped, and federally recognized”;

(ii) designating “[t]he National Guard of the United States” as “a reserve component of the Army of the United States” which “shall consist of * * * federally recognized National Guard units * * * of the several States” that “in time of peace * * * shall be administered, armed, uniformed, equipped, and trained in their status as the National Guard of the several States”; and

(iii) declaring “[t]hat the Army of the United States shall consist of the Regular Army, the National Guard of the United States, [and] the National Guard while in the service of the United States”.[1] Voluntary enlistment and being a component of the Army are, of course, incompatible with “Militia” status.[2]

Footnotes:

1.) AN ACT To amend the National Defense Act of June 3, 1916, as amended, Act of 15 June 1933, CHAPTER 87, §§ 5 and 1, 48 Stat. 153, 155-156, 153. See AN ACT Relating to the reserve components of the Armed Forces of the United States, Act of 9 July 1952, Pub. L. 476, CHAPTER 608, §§ 301, 601, and 701 through 703, 66 Stat. 481, 498, 501-502.

2.) The Sword and Sovereignty: The Constitutional Principles of “the Militia of the several States”, Front Royal, Virginia CD ROM Edition 2012, by Dr. Edwin Vieira, Jr., page 789.

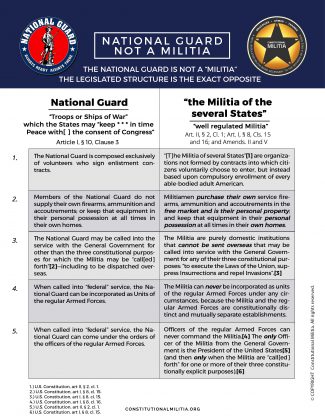

Congress has no constitutional authority whatsoever to prohibit the States from maintaining “the Militia of the several States”, in whole or in part, the National Guard and any so-called State “defense forces” must be, not any kind or part of a constitutional “Militia”, but instead “Troops” for the “keep[ing]” of which by the States “in time of Peace” Congress has given its “Consent”.[1] And if that is true in principle, then in practice all of the conditions and controls which Congress has attached to its “Consent” for the States to “keep Troops, or Ships of War in time of Peace” in the forms of the National Guard and the Naval Militia are presumably valid, because Congress may condition its “Consent” upon whatever otherwise constitutional requirements it deems expedient,[2] and may even permit the States to enact legislation of their own in order to implement the terms of that “Consent”.[3]

Footnotes:

1.) For example, the Virginia Defense Force is a small establishment (“with a targeted membership of at least 1,200”) the “mission” of which is “to (i) provide for a[ ] * * * reserve militia to assume control of the Virginia National Guard facilities and to secure any federal and state property left in place in the event of the mobilization of the Virginia National Guard, (ii) assist in the mobilization of the Virginia National Guard, (iii) support the Virginia National Guard in providing family assistance to military dependents within the Commonwealth in the event of the mobilization of the Virginia National Guard, (iv) to provide a military force to respond to the call of the Governor in [certain] circumstances”. Code of Virginia § 44-54.4. Obviously, the only connection between the Virginia Defense Force—in composition, organization, mission, and certainly pedigree—and the pre-constitutional Militia of Virginia is the word “Virginia”.

2.) See Arizona v. California, 292 U.S. 341, 345 (1934) (interstate compact).

3.) See De Veau v. Braisted, 363 U.S. 144, 153-155 (1960).

These developments expose some rather shady terminological double-dealings by Congress over the years, along the lines of political “bait and switch”—on the one hand, use of the verbiage “the National Guard while in the service of the United States”, which plainly was intended to invoke the constitutional provisions applicable to the Militia,[1] and thereby to lead the careless observer to conclude that the National Guard is somehow a proper constitutional “Militia”; and, on the other hand, use of the verbiage “[n]o State shall maintain troops in time of peace other than as authorized”, which no less plainly was intended to invoke Congress’s power over the States’ regular “Troops” as distinct from their true “Militia”. Nonetheless, at the end of the day, this serpentine statutory phraseology does tend to support the basal constitutionality of the National Guard as it is now organized. For if these statutes can avoid constitutional infirmity by reasonably being construed as positioning the National Guard within the “Troops” that the States may constitutionally “keep” “with[ ] the Consent of Congress”, and that statutorily may be deployed in the service of the United States without restriction to the three constitutional purposes mandated for the Militia, then they should be so interpreted.[2] For that reason, the Supreme Court was arguably correct to characterize “[t]he [National] Guard [a]s an essential reserve component of the Armed Forces of the United States, available with regular forces in time of war”[3]—although the Justices were apparently not perceptive enough to notice that, if the National Guard constitutes any“component of the Armed Forces of the United States”, it cannot be any part of “the Militia of the several States”. Yet that these statutes, even so construed, can avoid constitutional infirmity is not necessarily assured. For the States to “keep [their own] Troops” that simultaneously constitute “a reserve component of the Army of the United States” sets up a constitutional paradox which will require no little acumen to resolve.[4]

Footnotes:

1.) See U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 16 and art. II, § 2, cl. 1.

2.) See, e.g., Crowell v. Benson, 285 U.S. 22, 62 (1932); National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation, 301 U.S. 1, 30 (1937); Lynch v. Overholser, 369 U.S. 705, 710-711 (1962); United States v. Thirty-seven (37) Photographs, 402 U.S. 363, 369 (1971).

3.) Gilligan v. Morgan, 413 U.S. 1, 6-7 (1973).

4.) The Sword and Sovereignty: The Constitutional Principles of “the Militia of the several States”, Front Royal, Virginia CD ROM Edition 2012, by Dr. Edwin Vieira, Jr., page 792.

One does need to analyze these statutes with no little intellectual discrimination and skepticism. For they exhibit a distinct coloration of unconstitutional political imperialism on Congress’s part. For example, a subsection of the relevant section of the United States Code intones that “[n]othing in this title * * * prevents [a State] from organizing and maintaining police or constabulary”[1]—the implication being that, if it wanted to, Congress could “prevent[ ]” a State from so doing. But if a State’s “police or constabulary” were part and parcel of her Militia, as any such “law-enforcement unit” ought to be, or were some civilian agency necessarily separate in character from both the Militia and any State “Troops”, then Congress would have no authority to dictate to the State whether she could or could not “organiz[e] and maintain[ ]” such an establishment. Although, if a State’s “police or constabulary” were integral to her Militia, Congress could constitutionally “provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining” it, to prepare it (say) to be “call[ed] forth to execute the Laws of the Union”.[2] Only if the “police or constabulary” were separate from the State’s Militia, and of such a decidedly military cast as to be considered “Troops”, would Congress be entitled to dictate to the State the terms on which that “police or constabulary” could be “organiz[ed] and maintain[ed]”.[3]

Footnotes:

1.) 32 U.S.C. § 109(b).

2.) U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cls. 16 and 15.

3.) The Sword and Sovereignty: The Constitutional Principles of “the Militia of the several States”, Front Royal, Virginia CD ROM Edition 2012, by Dr. Edwin Vieira, Jr., page 792-793.

1.) An Act To promote the efficiency of the militia, and for other purposes, Act of 21 January 1903, CHAP. 196, § 1, 32 Stat. 775, 775 (emphasis supplied). Continued, An Act To further amend the Act entitled “An Act to promote the efficiency of the militia, and for other purposes,” approved January twenty-first, nineteen hundred and three, Act of 27 May 1908, CHAP. 204, § 1, 35 Stat. 399, 399.