Last Updated on October 1, 2021 by Constitutional Militia

AMERICANS’ DEEP AND ABIDING SUSPICION OF “STANDING ARMIES” EMBODIED IN “THE MILITIA OF THE SEVERAL STATES”

The Declaration and Resolves of the First Continental Congress in 1774, asserted “the keeping a standing army in several of these colonies, in time of peace, without the consent of the legislature of that colony, in which such army is kept, is against law”; and the Declaration of Independence in 1776, which enumerated as grievances against King George III that “[h]e has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures” and “has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power”.

Source: Documents Illustrative of the Formation of the Union of the American States, House Document No. 398, 69th Congress, 1st Session (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1927), at 5

“Standing Armies” Defined

“Standing Armies”

America’s Founders were philosophically, politically, and legally committed to the proposition that “the Constitution must either break the Army, or the Army will destroy the Constitution: for it is universally true, that where-ever the [military power] is, there is or will be the Government in a short time”.[1] Thus it was inevitable that, following hard upon their independence, Americans would embody these precepts and principles in their own fundamental laws.

“Standing armies”—whether of the traditional type, or composed of ostensibly “civilian” but para-militarized “police departments” and other “law-enforcement agencies”—cannot be trusted, because they tend to attract to, mold within, and advance through their ranks the very types of men and women who can be expected to side with and even egg on “ambitious and unprincipled rulers” against “the rights of the people”—to attempt to become such “rulers” themselves—and to exclude and weed out all other individuals who exhibit contrary inclinations.

“Standing Armies”: Abhorred and Denounced the Founding Era and Founding Documents

Because “[w]e are bound to interpret the Constitution in the light of the law as it existed at the time it was adopted”,[2] the condemnation of “standing armies” in the Declaration of Independence and various State laws of that period must always be kept first and foremost in mind.[3] Certainly the Framers of the Constitution evinced no lessor a strong aversion to “standing armies”.

These attitudes carried over into the drafting of the Constitution of the United States. For, as Virginia’s Governor Edmund Randolph reported to that State’s Convention, “[w]ith respect to a standing army * * * there was not a member in the federal Convention, who did not feel indignation at such an institution”.[4] This aversion and animosity were the products, not simply of historical erudition and acumen, but of profound political prescience. For although the Founders were never exposed to modern totalitarianism, they would have agreed that “[a]ccording to the Marxist theory of the state, the army is the chief component of state power”.[5]

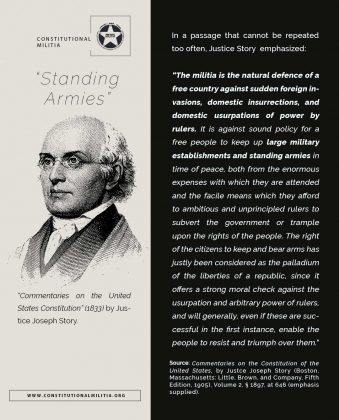

Against this background, the original Constitution incorporated and relied upon “the Militia of the several States”, not for the practical reason that America’s pre-constitutional Militia had always proven themselves perfectly efficient military forces (which in many instances they had not), but for the more important political reason that, being composed of WE THE PEOPLE en masse, the Militia promised to provide the most reliable “checks and balances” against the excesses of “standing armies” and the aspirations of usurpers and tyrants who would rely upon such forces to seize and abuse excessive political power. For, no matter how well organized, armed, and disciplined THE PEOPLE’S Militia may be, they will never function as “standing armies” in aid of usurpation and tyranny aimed at THE PEOPLE themselves. And the better organized, armed, and disciplined the Militia are, the better they can deter, and if necessary resist and overcome, “standing armies” raised by aspiring usurpers and tyrants in order to overawe THE PEOPLE.[6]

April 19, 1775, Boston. British General Thomas Gage’s imposition of “martial law” by means of a “standing army” left the patriots but one alternative: “We are reduced to chusing an unconditional submission to the tyranny of irritated ministers, or resistance by force.—The latter is our choice.—We have counted the cost of this contest, and find nothing so dreadful as voluntary slavery.—Honour, justice, and humanity forbid us to tamely surrender that freedom which we received from our gallant ancestors, and which our innocent posterity have a right to receive from us. We cannot endure the infamy and guilt of resigning succeeding generations to that wretchedness which inevitably awaits them, if we basely entail hereditary bondage upon them.”[8].

In the Founding era, no patriot dissented from the admonition “That a well regulated militia, composed of the body of the people, trained to arms, is the proper, natural, and safe defence of a free State” and “that standing armies, in time of peace, should be avoided, as dangerous to liberty[.]”[9] No less than George Washington himself, America’s first “Commander in Chief”, in his Farewell Address advised his countrymen to “avoid the necessity of those overgrown Military establishments, which under any form of Government are inauspicious to liberty, and which are to be regarded as particularly hostile to Republican Liberty”.[10]